Preparing for my trip to Terezin, a place which represents a point of deterioration along an inevitable trip toward death, proved impossible.

Visiting the Nazi holding camp is important, something that you’re just supposed to do. In trying to prepare myself, I became entangled in a mess of apparently inappropriate questions, namely wondering what I should wear and whether I should bring a camera.

I got on the van headed toward the Sudetenland, and ventured beyond the confines of the Czech republic’s cobblestone-marked capital. The first apparent difference between Prague and its environs is the prevalence of gas stations. Petroleum in post-revolution Prague stands as a symbol of personal wealth and potential prosperity.

To the Nazis, gasoline represented inefficiency. As a means toward the Final Solution (Endlosung in German), SS soldiers would drive, without destination, in a van roughly the size of the one that I rode in that Saturday on a sort of field trip.

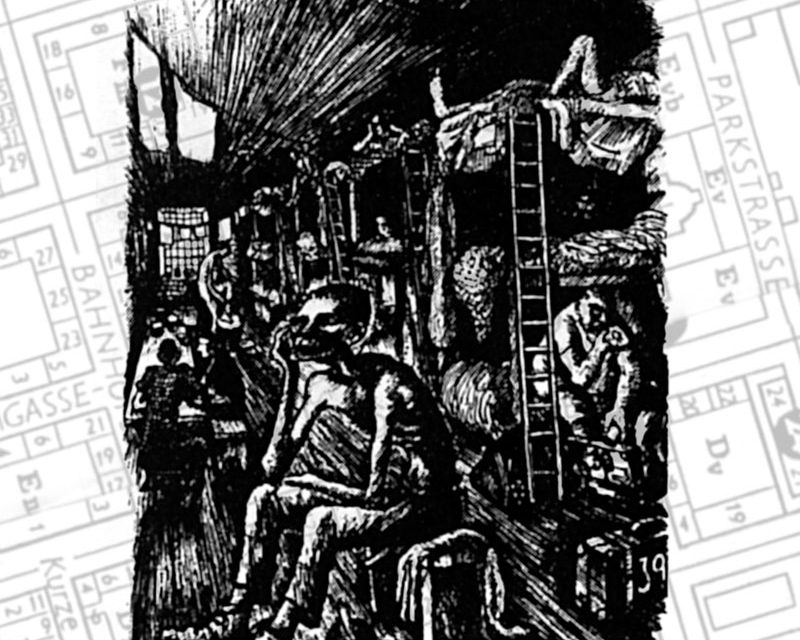

The front of the van was separated from the back with a steel barrier: the front occupied by two Nazi soldiers, the back crammed with up to one hundred undesirable citizens. The exhaust pipe was turned into the rear of the van, and the prisoners were driven around for twenty minutes-an allotment of time, calculated to insure a lifeless return.

These prisoners weren’t lucky enough to make it to “the Jewish transit concentration camp”, known as Terezin. My self centered expatriate dream collapsed immediately in four directions like a poorly constructed theatrical set when I remembered the method of extermination. I was on stage, and I began to understand how visiting Terezin was going to feel.

The Small Fortress at Terezin was built in the late eighteenth century as a citadel to aid in Czechoslovakia’s defense in the wars between the Hapsburg Monarchy and Prussia.

In 1941, the town became a rung in Hitler’s attempt toward total domination. In a manner consistent with Nazi methodology throughout Europe, the town of Terezin initially became a Jewish ghetto, then its Small Fortress was used as a prison, and ultimately it’s captives were sent to the eastern regions to be killed.

74,000 Czechoslovakian citizens were interned at Terezin between 1941 and 1945.

An investigation of the holocaust leads inevitably to the question of how. How did the entire world fall under Hitler’s spell? The answer is euphemism. This notion is particularly important in light of the discussion of propaganda.

A euphemism is, essentially, a lie.

A politician who uses euphemisms knows the true definition of what he is trying to say, but consciously molds his language so that his listener hears something quite different. When there is a clear distinction between one’s true and one’s professed aims, the euphemism is necessary.

In order to understand Hitler’s rise to power, we must recognize his skilled manipulation of language to obscure the truth. Hitler’s use of euphemism allowed millions of good, thinking people to tolerate the holocaust. The people knew he was an anti-Semite, but they did not know of his plan to murder every “filthy Jew” he could get his hands on.

They didn’t know because he didn’t tell them. He spoke of the “Final Solution,” and imparted to the disillusioned German people a feeling that all their problems would be solved. If he had spoken of his plans to exterminate an entire group of innocent people – the true meaning of “The Final Solution,” he would have been discarded as a lunatic. The euphemism worked.

The euphemism is a mask. With the proper construction of language, the mask is worn so effectively that the truth underneath cannot be seen. With propaganda, the terror of the holocaust was presented as a euphemistic, palatable reality. The walls of the Terezin fortress housed one of Hitler’s most effective tactics of propaganda.

In 1944, the International Red Cross began to scrutinize the actions of the Nazis, and Hitler knew he needed a stage. The Red Cross arranged a visit to Terezin, and Hitler set the prisoners to work painting the sets and the backdrops to create the facade of a bearable prison.

On September 11, 1944, Terezin was put on film in a piece entitled, “A Town Presented to the Jews by the Fuhrer.” The location was Terezin, and the actors were the prisoners of the Small Fortress. The film presented Terezin as a home, a place where all needs of the prisoners were met. The film depicted mothers with their children, partaking in crafts, and attending the recently built Terezin cafe. The children performed operettas and drew pictures, and their parents were proud.

The International Red Cross was appeased. I guess the conclusion was that if concentration camps were really all that bad, there would be no room for creativity.

I watched “A Town Presented to the Jews by the Fuhrer” in a museum that used to house a private movie theater for communist party members, and I knew for sure that truth is absolutely and ultimately subjective.

And then I walked away. I walked away knowing that the only prisoners to leave Terezin between 1941 and 1945, trod across its archway with an impending cognition of death so clear that it could be tasted on the tip of every tongue.

Educators and historians of the holocaust fear that with the death of its final survivors, the barrier against anti-Semitic cries of falsification will grow weak. It is feared that without living monuments and arms branded with numbers, radical Neo-Nazi groups will be able to make the holocaust disappear.

So we must remember, and we must visit Terezin and understand the subjectivity of truth and how it can make things disappear. Recognition of the horror of the holocaust’s victims and reverence to its survivors seems particularly crucial in the month of October, the home of the highest Jewish holidays.

It is necessary to celebrate a time where a young Jewish woman can walk out of Terezin and into synagogue to celebrate Rosh Hashonah and Yom Kippur. But the holocaust cannot be accurately categorized as a terror confined to the past.

This notion became glaringly obvious when I returned from Terezin and read the front page of a current Prague newspaper. The headline mentioned the forced sterilization of the Czech Republic and Slovakia’s “gypsies”. I became immediately aware that the reality of the holocaust is not a problem of the past.

Nearly half of Hitler’s victims were not Jewish, and do not belong to a religion that is now characterized by prosperity and freedom. The other six million people who were devoured by the jaws of the Nazi army were primarily these front-page “gypsies” and homosexuals. (Read more about gypsies and the Czech holocaust.)

“Gypsies’ are still perceived as ‘parasitic vermin’ who shouldn’t be allowed to spread their offspring freely across the Czech lands, and gay people still aren’t able to hold hands in public for fear of their physical safety. On the fifty-third October since Terezin’s liberation, we must reevaluate our scale of progress.