But after a peaceful stroll through the streets of Prague, where the greatest danger is a rerouted tram ringing its bell at you, the massive property damage of a True Lies or a Die Hard 3 can appear downright surreal.

Not that Czech film distributors offer many alternatives to these boom-n-boob fests. I n fact, I’ve often suspected the existence of some arcane trade agreement prohibiting American movies from entering the country with budgets less than $20 million. So it’s only natural for me to wonder how Czechs perceive some of our greater cinematic excesses.

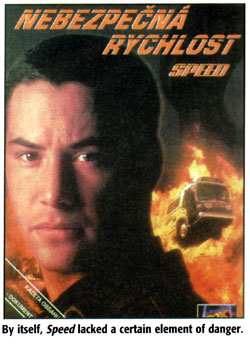

One indication may be in their choice of titles. In contrast to the less explosive nature of their own cinema, Czechs have I devised an informal labeling system for American movies not unlike our own ratings system. Simply: if the title of the latest I hyperkinetic release is at all boring or ambiguous-like, say, last year’s The Client I or Speed – then there’s a good chance it will have the word “Dangerous” tacked onto it for good measure. Thus: Nebezpecny Klient (“The Dangerous Client”) and Nebezpecna Rychlost (“Dangerous Speed”).

This rule also applies to titles with no literal Czech translation. So Narrow Margin, with Gene Hackman, becomes Nebezpecny Utek (“Dangerous Escape”), and Terminal Velocity, with Charlie Sheen and Nastassja Kinski, is rechristened Nebezpecne pady (“Dangerous Falls”).

And while “dangerous” may be the most popular choice in these cases, other qualifying adjectives have been known to add a little spice to (and give warning of?) especially heinous Hollywood action flicks. For example, Disclosure was known here as “Scandalous Disclosure,” while Outbreak – in case audiences had any doubt – became “Deadly Epidemic.” Most recently, the Sean Connery courtroom drama Just Cause found itself saddled with the nonsensically hyperbolic “Murderous Alibi.”

Speaking’ of nonsense, one of the more interesting side effects of this titling system is a seeming disregard for the original title’s meaning. Witness the Ray Liotta sci-fier No Escape, whose Czech title became the more hopeful “Escape From Absalom” and the William Hurt melodrama Second Best which the Czechs took the liberty of promoting to “The Best,” perhaps in an effort to beat Americans at their own incessant one-upmanship.

However, there’s an equal danger (no pun intended) of being too faithful to the original source. Examples of extreme literal-mindedness include The Chase, whose kidnapping story line bequeathed it the Czech title “Sensational Abduction;” while The Last Seduction, with Linda Fiorentino as a diabolical seductress, became, well, “The Diabolical Seductress.” An especially indicative transformation was Serial Mom – its Czech title: “Six Murders Are Enough, Mommie.”

On the other hand, such adjectivally unchallenged films as Indecent Proposal and Basic Instinct (which faced other, less correctable, handicaps) were perceived as dangerous enough without any warning labels. Thus we were spared Dangerously Indecent Proposal and Criminally Basic Instinct which would have taken us into exotic adverbial waters better left unswum.

Despite (or because of) their excessive nature and silly titles, these movies seem to enjoy a fair amount of success in this country. But what do Czechs really think of this schlock? Are they paying for tickets with one hand and thumbing their noses with the other? Or do these title changes reflect a genuine fear of American movies, – movies considered dangerous to the nation’s cultural welfare?

One ray of hope may be Barrandov Studios, which recently began distributing independent American films here, giving Czechs an opportunity to see there’s more to our movies than biceps and body counts. Although the company’s first release, the American co-production Death and the Maiden, leaves me to wonder: if even our good movies have such catchy titles, will Czech films have to follow suit? How long before titles like The Dangerous Ride and I Thank You For Each Deadly Morning arrive in a Czech theater near you?

It’s a scary thought. Maybe even a dangerous one.

This article was originally published in Velvet Magazine and is archived here.