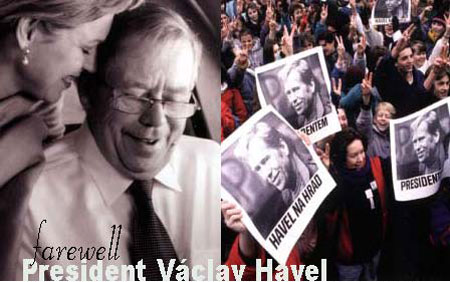

> The neon heart that shown bright above thePrague Castle, a replica of the one Havel often drew under his signature, was part of his farewell as president, a position he’d held since just after the collapse of communism in 1989. Like the president, the pulsing piece of modern art, which was put on display last November, has drawn a wide array of criticism and praise since the moment it appeared.

Whatever your opinion of the playwright-cum-politician, or his heart, one thing is clear: the country will not be the same when Havel stepped off into posterity.

And nowhere has that been more clear than in the strength the Czech Republic has on the western world’s radar screen. Havel is almost entirely credited with giving this small nation in central Europe a relatively big voice in both Washington, D.C. and Brussels. Since he took office as president of Czechoslovakia in 1990, Havel has won over three American presidents and far more world leaders.

Whether he was jamming with President Bill Clinton or waxing philosophy with French President Jacques Chirac, he made strong friendships and alliances with leaders that helped bring his nation greater prestige and power. But more than shaking hands and throwing parties with other presidents, Havel also did the roll-up-your-sleeves kind of work to accelerate the Czech Republic being brought into the western fold.

There is perhaps no greater example than his lobbying efforts to secure the nation’s invitation to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. After first suggesting the idea to Clinton in 1993, Havel turned up his efforts in 1997. And in 1998, he went to Washington, D.C. to meet with politicians one-on-one to convince them of expansion.

The following year, the Czech Republic became among the first of the former communist nations to join NATO. Indeed, the staging of last November’s NATO Summit here – the first to be held behind the former Iron Curtain – was an acknowledgement to Havel’s pull with his counterparts in the west.

During the two-day summit, Havel hosted a farewell dinner, in which he widely praised the dozens of heads of state who attended. Chirac described Havel as the “friendly, humble, soft but vivid light of the iron man who, in the dark depths of jail, in the abyss of totalitarianism, never weakened.”

It is this image of the dissident-playwright, who spent five years in jail, and was later exalted by the people to Prague Castle (“Havel Na Hrad”) that has captured the imaginations of western Europeans and North Americans for decades and contributed to the love affair many seem to have with him. Ironically, this persona hurt him at home. In his later years, many Czechs soured on Havel’s idealism and believed him to be out of touch and perhaps even egocentric.

But now that Havel’s days in office have passed, the Czechs are left with just the the two other leading statesmen: Václav Klaus and Miloš Zeman. Both politicians, former leaders of the country’s most powerful political parties, no longer enjoy voter popularity and compared to Havel, have relatively small standing on the world stage. (FYI: The president is elected through a vote in Parliament.)

Havel may be gone, but not his name or the influence, Havel stands poised to continue the icon of his nation and some say, his ideals may be needed now, more than ever.

Václav Havel, the Playwright

In today’s world, Havel is known primarily for his political involvement. As a result, we often take little notice of his accomplishments in the artistic realm. Prior to revolutionary political action, he surfaced to international fame as a playwright while working in Divadlo Na Zabradli (The Theater on the Balustrade) with the award winning play, The Garden Party (1963). Because of its success, Havel continued to write plays such as The Memorandum, The Increased Difficulty of Concentration, and Redevelopment. The fact that his plays were filled with blatant political criticism caused many of them to be forbidden in Soviet Occupied Czechoslovakia. Due to private circulation and secret performances, however, his works were very infl uential for the dissidents and intellectuals of that time. Since becoming president, he has been unable to continue writing plays. Devotees are left to wonder if he plans to write again upon leaving office. – Mary Hopkins