I fought it off for a good long time like a Hussite warrior. But I was doomed to this fate from the moment I set foot in Prague.

I’ve just been too energetic and displayed a pattern of conspicuous consumption that left me with nowhere else to go. There was that first moment of confusion, when I was awakened by the tram driver and pushed out into the cold.

I stood there shivering on a Bohemian winter night, looking at the warm tram sit idly for an eternity, waiting with a bunch of foul smelling bila whores until we could get back on and head back to the stops we had slept through.

End of the line. Bila Hora.

It is true that I have passed out before. Haven’t we all? I vaguely recall a drunken dawn when I took the metro to Malostranska and then got on the 22 tram, only to be woken up at Nadrazi Hostivar. I had gone the wrong direction, slept for 2 hours, and lost my favorite hat.

The institution of passing out is a foundation of Czech society, symbolized by Bila Hora. The mythology surrounding this place is great, and expands every time the 8, 22, and (especially) 57 trams reach the end of the line there.

The legend really begins on the 8th of November, 1620, when the Czech Protestant forces were defeated by the Austrians. This great battle was over in a single day. Bila Hora was outside the fortified city, but the Czechs made little if no effort to fight off their conquerors; they simply passed out.

In fact, the battle was the ideological fight of the Czech nobles and intelligentsia. It was based on high ideals, and fought by German mercenaries. The common Czech was hardly involved.

The rebellious estate leaders were hanged on Old Town square – where they are remembered today by white crosses next to the clock tower. Other nobles unwilling to re-Catholicize were forced to flee, and the church came up on their property. At this point Prague became Vienna’s b*tch, and German was officially put on equal footing with Czech.

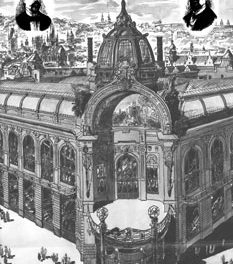

In The Book of Laughter and Forgetting, Milan Kundera describes the feeling of defeat: “… they swamped Prague with the splendor of baroque cathedrals. The thousands of petrified saints gazing at you from all sides and threatening you, spying on you, hypnotizing you, are the frenzied occupation army that invaded Bohemia three hundred fifty years ago to tear the people’s faith and language out of its soul.”

It would be another 300 years before the Czech nation regained their statehood. During the national revival period (1850-1900), the myth of Bila Hora was born. It became the great defeat of Czech culture, and the nationalist rallying cry.

Recently it was also the inspiration for this verse:

8, 22, 57 (nocni provoz)

Jedu tramvajem

unaveny ja jsem

budu spat na konecnou zastavku

protoze mam rad bilou horu

And may I suggest to Czech linguists that they recognize my creation of the verb ‘bilahorovat’. It’s hard to translate, but you get the idea.