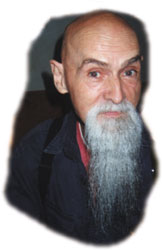

As deputy director of the Committee to Investigate and Document Communist Crimes, Zacek was in charge of unearthing crimes committed by the former communist regime. And what he found in yellowed memos and stacks of typewritten reports was the stuff of nightmares:

Kidnappings, espionage operations between Moscow and Prague and Prague and Havana, anti-demonstration techniques and assassination attempts.

Secret to most of the country for four decades, Zacek, 30, found and documented in public committee reports the hierarchy, terminology and techniques of the STB, the KGB’s "little sister" in the former Czechoslovakia. A "resident" was someone working from inside the STB. A "secret agent" worked outside, an ordinary citizen on STB payroll. During planned demonstrations, the STB would plant plain-clothes secret agents in the crowd who would suddenly turn on the demonstrators.

Yellow ribbons pinned to their shirts would distinguish them from the club-wielding police that would show up minutes later. "When I first started studying these files I was a little nervous," Zacek said. "I didn’t know what I was going to find about my colleagues, my friends, my family. You just didn’t know. " Zacek quit the post last month after a new director "politicized" the job and closed certain files, he said. But as Eastern European countries find ways to commemorate the 10-year anniversary of the fall of communism in their countries, Zacek has a memory or two to share.

As a 20-year-old journalism student, Zacek helped organize the now-famous Nov. 17, 1989, march down Narodni Trida, a main thoroughfare here, which ended with police attack dogs and more than a hundred students injured. The incident sparked the mass demonstrations on Wenceslas Square and led to the eventual collapse of the communist stranglehold.

Balding with a bushy brown mustache, wearing wire-rimmed glasses and short-sleeve shirts, Zacek looks more like a high school history teacher, less like a revolutionary. But as a student at Charles University last decade, Zacek was frustrated with his government’s oppressive communist regime and further dismayed by his country’s apathy toward it.

"There was no movement of the working class," he said. "Only the students seemed to be growing restless. We knew it was up to us to do something."

Near the end of 1988, Zacek and other students created the Student Information Center, a seemingly banal group of student leaders from the university’s different faculties. But by the start of 1989, the student group had turned political club. They would meet at Bily Beranek (White Ram) Pub, near Prague’s Old Town Square, and over rounds of Becherovka, discuss their views of the regime and their options on what to do about it. The group, which began with about 20 students, soon grew to more than 60 members and included students from Brno and other towns outside Prague. Word was spreading.

One summer day in 1989, Zacek was summoned to the STB offices on Bartolomejska Street, where he was questioned and threatened for three hours by two agents.

"One was the good guy, one was the bad guy," Zacek said. "They told me they wanted to stop these ‘dangerous’ activities of students, that they would just create problems in society. They threatened to throw me out of the faculty. We had planned an exchange trip to Western Germany and they said I would never go. I told them I didn’t want to see Western Germany that much anyway."

The student meetings continued, sometimes at the Bily Beranek, sometimes at the apartment of understanding parents. At one meeting in late October, someone suggested holding a demonstration to honor the 50th anniversary of a student uprising against the Nazi occupation of Prague on Nov. 17, 1939, where eight students died.

"We knew the communists couldn’t say no to that," Zacek said.

The students were given permission to gather, but not in downtown. They were allowed to meet at Albertov, a small square near the Vltava River, and march to the Vysehrad castle, away from the center of town. Nov. 17 was a bitingly cold Friday but Zacek hardly noticed as he arrived at Albertov at around 4 p. m. About 500 students buzzed with electric, nervous energy. Some held anti-communist signs, others waved national flags. The group began their march to Vysehrad, Prague’s first castle, but once there the crowd began chanting to turn the march downtown. They turned and headed to Narodni Trida ("National Street").

At the Ministry of Justice building on Vysehradska Street the students encountered their first line of police: a battalion of about 50 officers holding riot shields and dangling wooden clubs, standing shoulder-to-shoulder across the street. The students doubled-back and headed up the bank of the Vltava River. As they reached Narodni Trida, Zacek scrambled up a light pole to view the crowds. The group had swelled to several thousand, he said, a massive river of humanity bending right and flooding into Nardoni Trida. Workers and common citizens were joining in at every corner.

At the corner of Spalena and Narodni, the group ran into their second battalion of police, about 300 riot-geared officers blocking the street with armored vehicles, Zacek said. From the rear appeared another squad of police and suddenly a chunk of the group was pinched off, surrounded by police. With nowhere to go, the demonstrators stood calmly for about two hours, and began singing songs, a massive rendering of the Czech national anthem.

"That was the first strong feeling I had, when everyone starting singing the Czech national anthem," Zacek said. "The second was when they attacked."

The push came from the rear as police began to squeeze into the crowd. An armored police car from the front started a simultaneous push. There were no side streets, nowhere to go. The police infiltrated the crowd, swinging wooden clubs, kicking, and punching. Panic erupted in the crowd. Zacek watched as a group of police waited on one end of a covered walkway on the sidewalk and swung their clubs on emerging demonstrators, the clubs cracking down on collarbones, forearms, legs.

Zacek scampered on top of a car to escape the crush. "There was no more street, just people running," he said. He saw a group of police, dressed in camouflage green and red berets, identified later as anti-terrorist specialists, attack one woman with expert karate chops and kicks. German shepherd attack dogs came next, biting and snapping randomly at protestors. A friend was handcuffed and thrown inside a police bus, which disappeared down a far street. Another protestor was yanked from inside a telephone booth where he was hiding and beaten to the floor by the red-beret police unit.

The entire incident took less than 30 minutes, Zacek said. When it was over, more than a hundred protestors laid injured across the street. Inside the covered walkway there was a pile of blood-soaked T-shirts, women’s slips and boots left hastily behind by protestors. Zacek helped Ladislav Lis, a well-known dissident, pick up the clothes to present later as evidence.

The next morning, Radio Free Europe and even CNN were broadcasting early news of the march. Zacek met with other leaders of the Student Information Center at a friend’s apartment and stayed up until 1 a. m. drafting a former protest and declaration of a nationwide strike by students. The strikes began the following week. By mid-week, hundreds of thousands of Czechs (students, workers, mothers, teachers) were pouring into Wenceslas Square calling for the resignation of the communist party.

On Nov. 24, exactly one week after the march, the communist Politburo did just that. Czechoslovakia was free.

In January 1990, a friend showed Zacek how to research through the newly-opened STB files. Zacek was hooked, having found a use for his journalistic skills and love for history. He started by printing the names and pictures of former STB agents in his student newspaper, Studentske Listy. Then he wrote about their techniques. By 1993, he was offered a job at the Committee for Investigation and Documentation of Communist Crimes.

Zacek said he wants to continue his work outside the committee. He plans to start a similar civic group called the Independent Institute of Communist Totalitarianism. For now, he spends much of his time with Society ’89, a non-profit group dedicated to commemorating freedom from communist rule.

"It’s important that people remember," Zacek said over cappuccinos at Slavia Cafe, a former popular watering hole among dissidents. "There are people who will say the communist system failed because of a few bad people. But the regime wasn’t bad because some people committed crimes. It was a system organized to commit crimes. That’s what I want to show. Some people tend to forget that," he said.

He looked out over the people in the cafe and beyond, to the busy crowds outside on Narodni Trida, his mind many years away.