(To be read while listening to “Waitin’ Round To Die” by Townes Van Zandt)

One less pub in the world tonight and we’ve each got about $250 jammed down our socks. How did this happen? I was just drinking a beer, fresh from being “let go” by the cheapest American I’d ever worked for.

Peter was behind the bar, serving for free out of boredom and wrath, his own boss sunk in a noisesome drunken conference in the back room; another miserable opportunist.

The relative success of certain people who were here at the right time with the right money seems to have given them carte blanche to act like pigs on the basis of primacy.

“I’ve had it here,” said Peter, scraping the head off another Staropramen. “Let’s just ditch the flat and f*ck off somewhere sunny. I’m sick of the poverty and the smell of sweat.”

He was right, in a way. Out in Strasnice even the steel walls of the tram cars reek of the sweat of years of toil. The buildings themselves are exhausted from the labour of standing erect. Doors creak with knobs worn beyond rust by hard-caloused hands, paint chips fall from the walls and ceilings like dead birds when no one’s watching. I can see what he’s saying, but it’s no better to be poor in a rich country and much more hassle in the bargain.

“Want to go to Romania?” I ask, “the Black Sea?”

“Are there beaches there? If there’s beaches it’s good for me. The sunshine is the thing.” His eyes were suspiciously empty as he spoke. “Anywhere is good for me.” I had a loose plan to follow anyway. A five year plan which would see me to the east end of Asia if I stuck to my guns.

He gave me a conspiratorial glance and served the beer out to some monkey’s girlfriend. She tapped a pack of Marlboro lights out on the solid stained-oak bar. Her boyfriend was off taking a piss – staring vacantly at the row of “Red Light Praha” girls plastered to the wall above the urinals. Maybe she was lost in thoughts of home, or trying to reckon the days of travel. Her eyes were darkly circled and, for some reason, I imagined I felt empathy with her.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

"Rockville, Maryland." I try to picture Rockville, anything specific. All I could conjure was a vague chronology of strip malls and an REM song.

“How long have you been travelling?” she asked, a little more than indifferently.

“I’m not travelling. I live here.”

I watched the way she greeted her boyfriend, who seemed to have been in the toilet for ages. A shift of the hips, a blink and unmoving eyes. He assessed me quickly, frowned and sat down. They’d met at school. They’ll probably marry in a year or so and base the rest of their fantasies on the freedom they thought they remembered from some vague time.

I suppressed the urge to whistle “Don’t go back to Rockville… and waste another year…” I don’t have anything against this life, or even pretend to see that deep inside it. I am, perhaps, a little bit jealous of the way the world seems to fall into place for those people.

They always have the right jacket when it rains and remember to pack everything they need. I see them everywhere, eager to dig their way home through the solid current of foreign architecture as if fulfilling some biological imperative. Compulsory migrations. We all collide in the smoke-choked bore of an Irish pub in the Czech Republic.

At half three Peter closed the door and locked it. I laid out the last of my cash on the bar for the remainder of the Bushmills and the money sat there as we drank. Then we were in the back, counting out money from the safe, working on a bottle of Vodka. To suggest that something was wrong seemed superfluous – it would not have been enough.

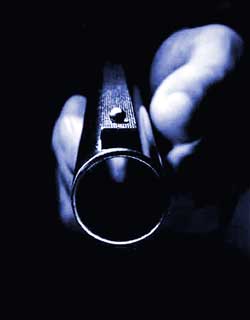

Peter took the money, folded it into his bag and tossed the keys to the safe out the window, where they splashed silently and irrevocably into the canal. Lost forever. All the remains of a normal life – the well-packed bags, the perfect haircuts, fade out with the sudden shock and thrust of a shotgun blast. We were off to Romania with not a word spoken on the matter.

Or maybe to Hungary. Or maybe steal a boat and just float down the river to who knows where. We’d cross that bridge when the trusses opened our foreheads. Now we had to pack, buy tickets, get sober. We laid out all our things on the floor of the flat in a circle around us. Bottles of drink, a handful of cigars, clothes and half-empty tubes of toothpaste. We’re on ground zero, the monkeys in the middle are trying to salvage some scrap of structure. This is yet another cloying vision of Prague; a desperate feeling – like waiting in line for bread, looking at shelves with a few boxes of lightbulbs, a bag of onions and a plastic baby doll peering out from under polychemical hair.

A young girl turns a corner and stops; remembers the sour tang of turned ice-cream that came in one flavor and once made her sick. A pensioner pokes doubtfully at the buttons of a display model mobile phone.

Sometimes the past and present cross and swallow each other. The air still holds the loose form of collapsed statues, hung in static. The bags are packed and there’s not space for the last bottle of Absolut, so we call a taxi and drink it down while we wait.

Crossing the street to meet the taxi I feel a twinge like homesickness, like seeing a campfire from the opposite bank of a river at night. I direct the taxi through the tangle of streets in the old town to Marshall’s tea garden. Everything moves like the final ten minutes of a television program – I dump some bags in the dank basement of the shop, ask Marshall for advice on Romania, run a few scattered errands while Peter is off changing the money to dollars and finally collapse at a table and order one last pot of tuareg for the road. My head is spinning and ghosts are calling out from all sides.

The vodka is elusive, it suggests clarity.

Peter stumbles in with two tickets to Bratislava. Not quite Romania, but a step in the right direction anyway. We say our goodbyes to Marshall and I snap a quick photo of Peter creeping up behind the fake sheep in the garden with his belt unbuckled and a bottle of something in his hand.

“Oh, and why don’t you come on in to work today as well lad?” he screams. At 3 in the afternoon we’re on the train, watching Smichov fade away behind us. I took off my boots and stretched out in the first class compartment. Floating silently through gentle hills. Trying to read the Brothers Karamazov and losing my line every other word. The train is a holding pattern, the first television.

We are dumb pioneers, smiling at the camera, unmoving as the sun goes down. We slip through pattern, the first television. We are dumb pioneers, smiling at the camera, unmoving as the sun goes down. We slip through sheepfolds and open fields, towns and backyards like ancient thieves practiced at the art of invisibility.

The railroad engineer must have the most lonely job in the world – sitting with the controls, staring out on the blackness of passing earth. One would fall to contemplating the markings of the various dials, their relative levels of wear and absolute meaning. The engineer at night – no steering, just speed crossing the night. A sobriety passed over the cabin as the novelty of movement subsided.

Peter stared at the passing villages – points of light in space. Perhaps he was seeing the fields of the Irish midlands for the first time. Trying to divine the nature of someone you travel with is a continual guessing game, as I would confirm many times over in Peter’s case. On the road we become all people; only arrival is confusing and only returning is anonymous.

Peter shifts out one of his infamous farts, a ripping portent that breaks our hours of silent thought. I jump up, crossing myself, and yank the window down along its rusty rails. “F*cksakes,” I say, gulping in the outside air and listening to my papers blow around the cabin.

Crossings Part 2

The door to our compartment is jammed with border guards. “Pass,” they demand in one voice. “Pass.” Our journey to Slovakia has been an endless absurdity of paper checking. First tickets, then passports, then tickets again. One of the bunch managed to figure out that we were sitting in first class without the appropriate tickets, a situation I tried to remedy with an American $10 bill.

“No,” he insisted, steadfastly refusing to take anything less than 200 Czech crowns. We bought tickets to Budapest on the spot from the same honest man. A few hours later, we rolled into Budapest. A terrifying soup of thieves, hippies and backpackers, Budapest’s main station woke me up. For the first time since leaving Chicago, two years ago I feel the patchwork mass of a real city hanging in the air around me. Peter and I struggle over to the Change office with our bags, where we are immediately accosted by Victor, a Tarantino-mouthed hostel envoy who promises to show us all over the city if we register at his hostel.

Crossing the Danube on a sweaty city bus, shafts of sunlight trace the paths of tiny boats below. The relative similarity of bridges crossing rivers. The language surrounds me with a trickling reminiscent of the subtle adjusting sound a train akes on a trestle. Peter and Victor spot an advertisement for McDonalds, which sets off a thoughtful discussion of the ubiquitous American cultural presence.

“The sh*t is f*cking everywhere man,” Victor waves his arm out to encompass the entire city. “America has no culture, just products.” Peter nods in agreement and I say nothing. On the train, I read about a certain museum in Vienna where visitors can parade past a man, sliced along the longitudinal, into a thousand, paper-thin slices.

The hostel was typical – a university dormitory left vacant through the summer. They sold cheap, plastic waterguns at the reception and we all bought one. Peter and I checked in, left our bags and went off in search of drink. Victor had some “f*cking business” to attend to and left us with directions to “The Old Man’s Pub,” where we would meet him later for “some f*cking beer.” He pointed his watergun at Peter, “Bang”.

Cue Dick Dale.

No matter where I am, there never seems to be a shortage of irritating tourists from my home town. Muffy and Buffy joined us at the first bar we stopped in, tossing their Jansport bags down on the bench next to us, cheering Peter sufficiently to make him order another round. The usual barrage of questions followed and I let Peter answer, absorbed in a map of downtown Budapest.

“Where are you from?”

“I’m Irish, he’s American.”

“What are you doing here?”

“We came to rob, rape and pillage.”

“Oh, is that the name of your town?”

“No, we’re on the run from the law.”

“Oh. I don’t think we’ve been there.

(A quick glance to curious companion confirms this) "Where did you meet?”

“In prison.”

“Have you been travelling long?”

“I’ve always been travelling.”

“Where are you going?”

“To the end of the line.”

I look up from the map long enough to catch a glimpse of Buffy’s driver’s license as she searches her wallet for cash to buy another round. Winchester, Virginia. Horses and barns parked full of undriven cars. The Patsy Cline museum.

Eventually we leave, Peter’s arm wrapped around Muffy’s waist, Buffy casting approving glances at her sister. “Oh, his accent is so cute.” The Old Man’s Pub crawls out of the side of a building at us, vomiting drunken students into queued taxicabs, and it’s not even ten o’clock.

We secure a table in the center of the dance floor and the girls carry themselves off to the bathroom. Peter turns to me, “I don’t fancy her, no, I think she’s a bit ignorant.” The lack of female companionship was one thing he’d been complaining about for months and I reminded him of it.

“Let’s just have a few drinks and see how it goes,” I said.

A few overpriced beers, laden with the peculiar stench and weightlessness of Italian brews, later he leans away from Muffy and whispers in my ear, “It’s only the fat one that’s into me anyway.” Trouble creeps from under the bar.

Buffy (the skinny bird) rakes my shoulder on her way to the bathroom (for the third time in 30 minutes) and I leave Peter and Muffy to follow her. A huge mirror with common sinks for women and men, the persistent aural void of urination. She pulls me against her and initiates a drunken kiss.

She’s wearing earrings with diamonds set in them when Peter stumbles through the swinging door, takes a look, then slams it on his way out. Trouble turns the lights dim and yellow. We make our way back to the silent table, where the girls fall to looking “meaningfully” at each other and rubbing their arms. Peter stares at the approaching waitress.

“I’m gonna rob the mutherf*cker,” he says to the table, drawing his knife from a coat pocket. The girls giggle nervously as the waitress approaches, then Muffy sees the knife under the table. She drops her beer, Buffy screams and grabs her bag. The waitress, oblivious, leans over Peter to help clean up the mess and he grabs her by the arm, pulling the knife out into plain view. “All the money! Now!” Peter screams at her. The girls throw some monopoly money on the table and run for the door.

Trouble picks up the Louisville slugger from under the bar and approaches our table, but no one in the pub has any idea what’s going on. They start slipping out the door, tabs unpaid. The tattoo on the barman’s arm says something in Cyrillic. I grab Peter and try to drag him to the door, but there’s a fire in his eyes, “Let’s rob the mutherf*cker!” he screams again. I slip out the door just in time to jump into a taxi with the girls. The crush of plastic, a shocking wetness. The watergun had snapped in my pocket and drenched the seat.

“What is wrong with your friend?” Buffy demanded as the cab started off. I tried to explain a little bit of Peter to the girls, but I might as well have not even tried, for all their chorus of “that’s no excuse.”

They saw no excuse for anyone to be different from them, in the end. It’s one thing to watch that kind of thing in a movie theater, but real life is different; more like them. Just as we turned the corner, Peter ran into view. No one was following him, he was just charging down the street, full steam. I asked the driver to stop, but Peter wouldn’t get in.

“F*ck them, I’m not going anywhere with those boring little b*tches! Let’s go for a drink somewhere else!” He runs off down the empty street and we head for the hostel without him.

The sisters have recovered enough to have a nightcap at the hostel bar by the time we get back. After a few minutes of silence, they start in with that embarrassing “code-talk.”

“Do you think I should go visit that friend tonight?” Muffy asks Buffy, winking a little bit.

“Oh no,” says Buffy.

“No.” Muffy looks at her. “I’ll be really, really upset if I don’t go see that friend tonight.”

This is boring. Maybe I should have gone for another with Peter. Mid-sentence, I run my hand under Buffy’s skirt and stare blankly at the picture of the Roman baths hanging on the wall opposite. She continues her conversation, I continue feeling her up. Her sister finishes her beer and looks at the bottle, tilting it, almost letting it drop. Buffy emits weird little gasps, shifts a little on the bench. The bartender switches radio stations and The Pixies blare mercifully from the ruptured speakers.

Muffy grabs her things and heads upstairs. Buffy leans in for another drunken kiss, but I push her away. I’m alone in the elevator, heading to my room, thinking about the Huckleberries, about sitting out by the railroad tracks in Manassas, passing a joint, talking about the future between the mad rushes of deafening trains.

“In ten years, if we aren’t doing anything else, we’ll all meet in Texas. We’ll buy the ranch, put huge speakers up on every hill and play The Pixies all night long and screw the neighbors. We’ll smoke pounds of weed and go blind watching every sunrise, stay up late.” We shook on it with blood, pricked from fingers by a sharpened twig of lilac growing along the tracks. That was ten years ago, and I don’t know where one of the five of them is today, myself included.

The door to the room is locked and I can hear Peter, snoring away inside. I pound on the door, but his rhythm doesn’t even flinch. I try my key, but the lock won’t turn; he must have left his key in the door. I head back downstairs.

“Your friend was very drunk,” the receptionist told me. “Yes, I know, but I have to get into the room.” I knew I could climb in the window from an adjoining room, neither of which were occupied.

“Can I have the key for 202?” I asked.

“Passport,” he replied perfunctorily.

“But my passport is locked up in my room!” He grinned at me stupidly, then asked for a deposit, so I reached over the counter and grabbed the key. “I’ll be right back. Just sit down and shut up!”

I went through the window in the open room, happily buzzed, feeling the warm summer breeze pushing against my back. The curtains blew out after me, dancing with the drapes from our room. The window was open, and I fell breathlessly into the black room after a short skitter along a thin ledge, and was instantly overpowered by the stench of beer. Broken glass crunched beneath by feet as I crossed the room to cut on the light.

Peter was passed out drunk on his bed, the handle of his knife sticking from the slaughtered mattress beside him like a fencepost. The room was in shambles – broken beer bottles and dirty clothes swim in pools of stale beer. It looked like we’d been squatting the place for weeks.

I kicked the remains of a bottle, spinning it across the floor to shatter against the leg of a desk, and Peter just snored away, dreaming of a pub with free beer and a thousand girls on his arm, gathered round to hear tell of the time he “robbed the mutherf*cker.” I had to laugh I guess; there were Motley Crüe posters on the wall. There’s always a line, always a time to cross the line. Peter liked to leave the line bleeding on the floor.

The next morning Muffy and Buffy walked past us without a word. Peter and I had decided to get out of town for the big solar eclipse – the eclipse that signaled the end of the world, according to some interpretations of Nostradamus.

Scores of festivals were sprouting up around Balaton, the Hungarian sea and, supposedly, the best place in the world to view the event. The train we boarded was packed to the gills with backpackers and tourists.

A solar eclipse occurs when the path of the moon crosses between the earth and the sun, throwing its shadow over the globe and causing the blackness of night in the middle of the day. It’s a hell of a thing to see; it’s like the end of the world. But then, almost anything is when it happens at the right time, in the right place and nothing at all can stop it.